Highlights

- Prayerlessness is now a majority-phenomenon among young females in the UK and Belgium. Germany and Spain are near the tipping point. Post This

- Women who pray daily have 0.2 more children than those who never pray. When averaging across both men and women, the difference rises to 0.3. Post This

- A 2% increase in GDP per capita raises fertility by 0.0081—the same effect as a mere 1.12 percentage point increase in the share of women who pray. This suggests that faith is as important—if not more so—than economic fundamentals in determining fertility rates. Post This

This past summer, I heard about a new book on demographics, After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People, by American economists Dean Spears and Michael Geruso. The authors suggested to me that we start a conversation about population decline (and how to reverse it). A few weeks later, I visited Chengdu, China. Asking about the political landscape in this part of the world, low fertility rates were the topic of choice in the first few conversations I had. This illustrates how informed views on demographics are simultaneously shifting in many places.

For a long time, low fertility rates were seen as necessary for development. Talk of a demographic dividend is still ripe. And economists had their own theory: the quality-quantity trade-off whereby the newborn child would negatively affect their older siblings’ lifetime earnings by diluting human capital investment. It’s a persistent story and one that I see with skepticism. If there was a quality-quantity trade-off, shouldn’t only children dominate first-borns in terms of outcomes as more resources are available to guarantee their success in life? A meta-analysis of empirical studies, by contrast, shows no rivalry, no differences in outcomes between only children and first-borns.

Shakespeare once said: The world must be peopled. Many of today’s economists seem to agree. Or at least they understand compounding. Four children born for every three women (one childless woman and two women with two children each) means that the population more than halves every two generations. Our pipeline of talent, imagination, joy, and GDP-enhancing innovations is dwindling. This, however, is happening globally, and especially so in the most developed parts of the world. (See this great presentation by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde.) If you haven’t noticed yet, chances are you live in an urban agglomeration whose younger ranks have been swelled by a now-depopulated countryside.

Why Aren’t People Starting Families?

Why do so many more young people choose not to start families? Why is the average family size shrinking? And why is it shrinking everywhere—in countries with generous parental support (e.g., northern European welfare states), and those without it (e.g., the Americas)? The economics profession by its own admission has no clue. While presenting the book at Wellesley College, Michael Geruso commented that those who say with certainty why this is happening are probably wrong. In a way, that is funny. Because when Dean Spears reached out to interest me in the book, the first thing I did was to offer an explanation. I wrote then: “I think that fertility declined in sync with a generation exchanging their Judeo-Christian heritage for an economic project (house, career, status).” In hindsight, I wish I had expressed myself more clearly, especially because my theory is simple: people have children because they pray.

How Prayer Changes Us

If you do not pray, it will be hard for me to explain why I think this way. Prayer is one of the most powerful things that happens to me during the day. Sometimes, the urge arises suddenly as in the silent prayer during a conversation that has taken a serious turn: “Lord, let me speak with love, not pride.” Or “grant me patience” when demands pile up as they so frequently do with children. Prayer can be triggered by sad news, as in personal loss. Or when the Colombian people rejected peace in a referendum. Only God could soften the hearts of the Colombian people so that they could forgive past evil and reconcile. Prayer is a human instinct. And much like other instincts—dance movements, a mathematical proof by contradiction, musicianship, or the perfect serve in tennis—it is learnt gradually. To what effect?

My theory is simple: people have children because they pray.

Mother Teresa explained the transformational role of prayer this way: "The fruit of silence is prayer, the fruit of prayer is faith, the fruit of faith is love, the fruit of love is service, and the fruit of service is peace."

In the language of economics, Mother Teresa highlights two distinct channels through which prayer operates.

Prayer and Preferences: First, prayer changes preferences. Before we pray, our actions may reveal that we prefer bundle A over bundle B. After we pray, no more. The direction of this change is from self- to other-regarding: Prayer transforms the faithful to desire a life in the service of others. This is not just a theological belief but also a theory with Popperian predictions: If true, prayer ought to increase many forms of service to others—volunteering, charitable giving, and care for elderly relatives.

I invoke the theory in this post on demographics, because raising children represents one particularly happy form of service (although by far not the only one). There is suggestive evidence, I think, that the transformation caused by prayer shows up in the data. The faithful work fewer market hours, but a greater number of non-market hours caring for others.1 This very shift toward non-market activities—including childrearing—may be precisely what matters for fertility. Said in a more perfect way, if we pray that God makes us an instrument of his divine love, perhaps this has empirically measurable consequences?

Prayer and Subjective Beliefs: Second, Mother Teresa suggests that prayer, through faith, changes subjective beliefs. If God has created the world so that we humans could share in his wisdom, goodness, and being, then his creation could impossibly lack what we need to thrive. A person of faith may fear catastrophic events, but protected by God’s grace, does not place high probabilities on them. Only an atheist could have written a book such as the ‘population bomb.’ A person of faith would have placed their trust in divine providence instead.

That prayer transforms goes beyond belief. Popper's scientific method tells us to seek out empirical evidence. (And so does scripture: 'by their fruits you shall know them.') Can prayer re-people our kindergartens, rejuvenate family celebrations, and give new life to dying villages? For lack of studies on this question, I looked at the data myself.

Rising Prayerlessness in Europe

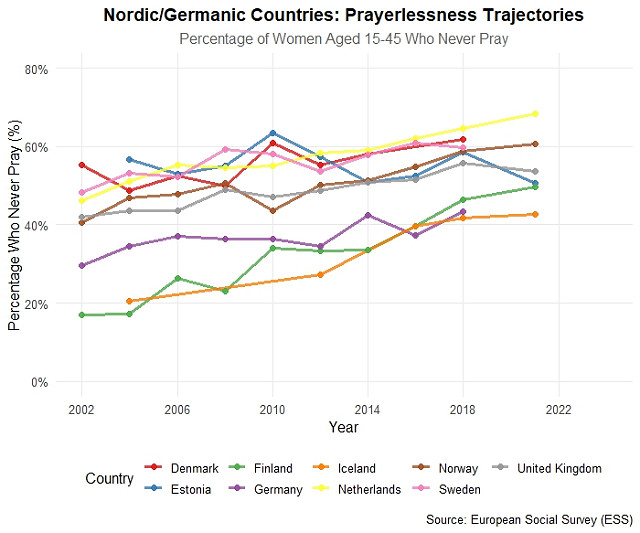

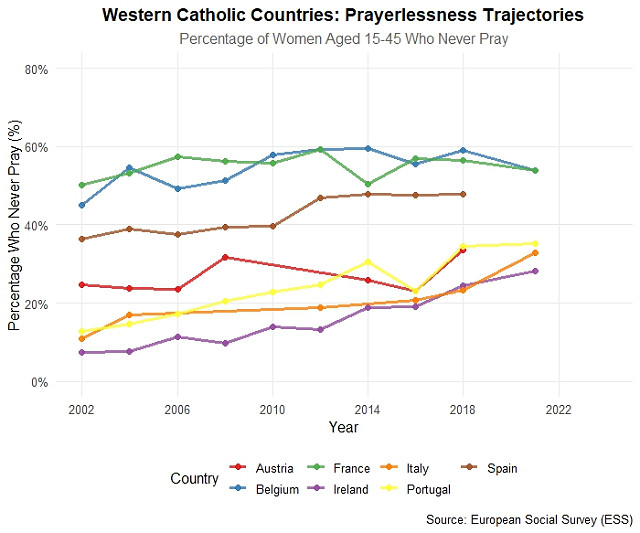

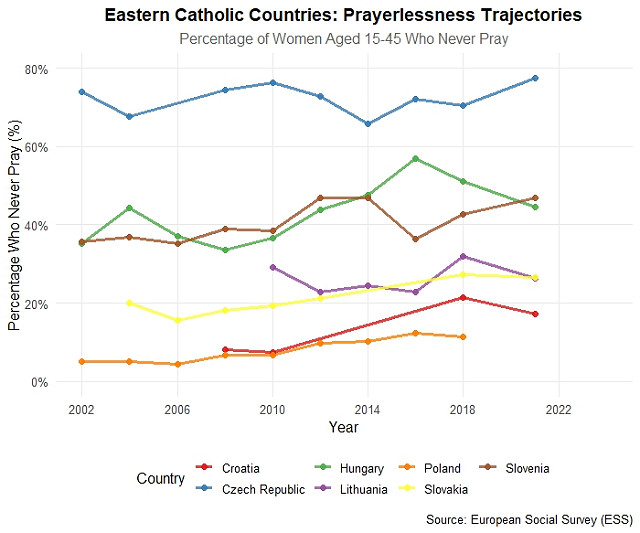

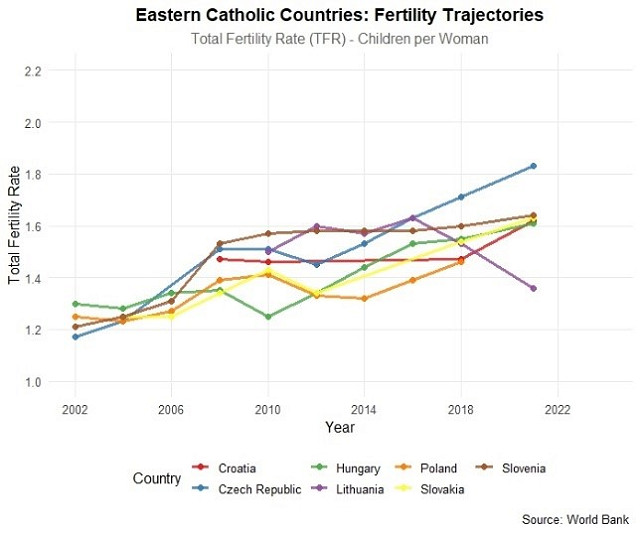

Data on the frequency of prayer is not hard to come by, at least as far as Europe since the 2000s is concerned. The European Social Survey, run every two years since 2002, holds many answers. To track the fertility rate, I computed the share of 15- to 45-year-old women (that is, women of fertile age) among survey respondents who reported that they never pray for each surveyed country (specifically: EU, Switzerland, Norway, UK and Israel) and for each of the 11 surveys between 2002 and 2024.

The descriptive statistics reveal a recent rise of irreligiosity in Western but not high-growth Eastern Europe (see figures below). In 2002, there were only three countries where only a minority of 15 to 45-year-old females prayed: Denmark, Czech Republic and—just barely—France.

Everywhere else, the majority prayed: Prayer was widespread in the Protestant Nordic countries, especially so in Finland. Likewise, supermajorities of at least 2/3 of young women reported praying in the traditionally Catholic countries of Italy, Ireland, Portugal, Austria, and (part-Catholic) Germany. Twenty years later, those supermajorities only exist in Ireland. Iceland is the only Nordic country where a majority of females in this age group still prays.

Prayerlessness is now a majority-phenomenon among young females in the UK and Belgium. Germany and Spain are near the tipping point.

The rise in prayerlessness is surprising and warrants further investigation. Why deprive oneself of hope? Individuals’ personal religiosity correlates with various measures of well-being, happiness, and mental (and, in some instances, physical) health. (See for instance here, here or here.)

Prayer and Childbirth

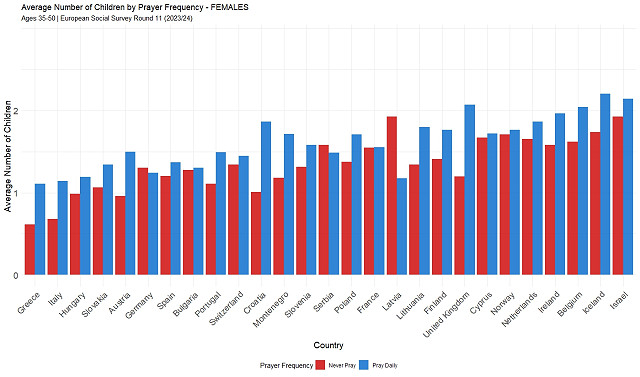

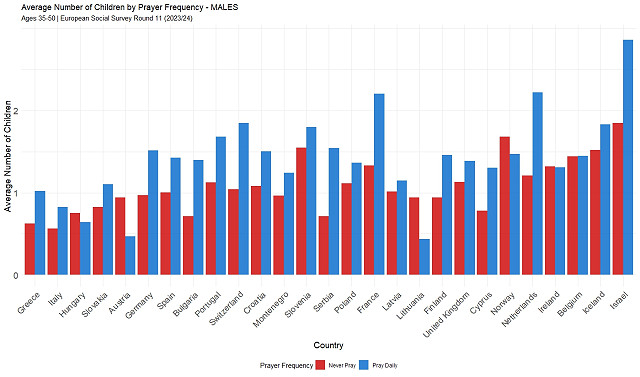

Religiosity also correlates with childbirth. In the European Social Survey, respondents do not report the number of own children. The survey does, however, collect information on the number of children in the household. Looking at 35 to 50-year-olds only in the latest 2023/24 survey, we may infer a very rough estimate of fertility rates. Women who pray daily have 0.2 more children than those who never pray. When averaging across both men and women, the difference rises to 0.3.

The figure below shows the average number of children by frequency of prayer for women only across Europe. (Please click on the figure to see a higher-quality image of both men and women).

This figure shows the average number of children by frequency of prayer for men only in select countries (again, click on the figure for a higher-quality image that shows both men and women combined).

Does Prayer Explain Fertility Differences?

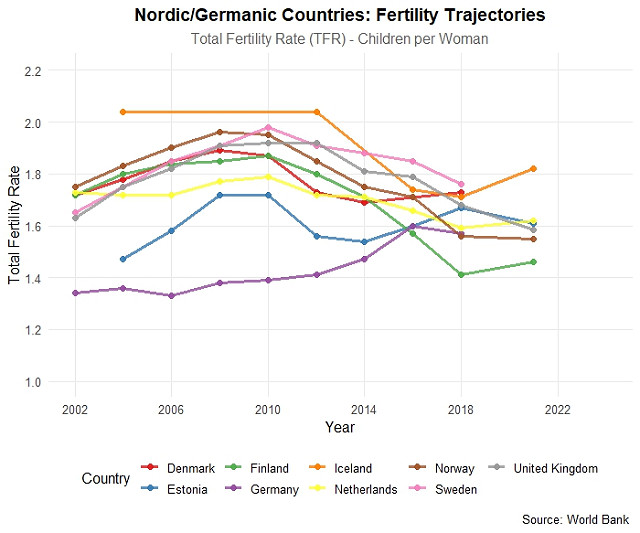

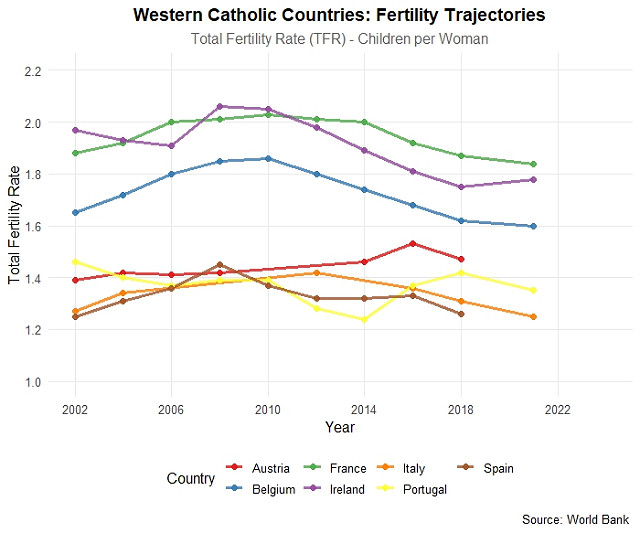

To study the link between declining fertility and rising prayerlessness in Western Europe since the early 2000s, I analyzed panel data from the European Social Survey combined with World Bank fertility and GDP data. I controlled for country-specific historical factors (like Communism and war experience) and time-specific shocks affecting all countries simultaneously.2

The results are just as the theory of transformational prayer predicts—countries where more women stop praying see fertility decline. The effect is statistically significant and substantial: a 1 percentage point increase in the share of women who never pray is associated with a fertility decline of 0.0072 children per woman. To put this in perspective: a 2% increase in GDP per capita raises fertility by 0.0081—the same effect as a mere 1.12 percentage point increase in the share of women who pray. This suggests that faith is as important—if not more so—than economic fundamentals in determining fertility rates.

The effect size of prayer relative to GDP challenges common explanations of low fertility. Conventional narratives center on socio-economic determinants: urban migration, educational expansion, welfare systems, and gender role changes. But Europe's economic and social structures were largely mature by 2000. The gender revolution in higher education was complete by the 1990s, as was urbanization. Nordic and Continental European welfare systems were established decades earlier. This makes the synchronized decline in both religious practice and fertility more difficult to explain through alternative channels.

Faith or Tradition?

Sympathetic observers with whom I’ve shared my results are quick to argue that higher fertility rates among the religious are plausible; however, they should be attributed to cultural norms linked to religiosity, not active religious practice. This is certainly possible. But how would we know? Polite society’s taboo not to talk about religion only ensures that the question remains unanswered.

Keynes famously argued that ideas change the course of history. I agree. Ideas are powerful. But only so if they are believed. A norm, lacking belief, has the qualities of a decapitated chicken: it might keep on running for show, but won’t overcome obstacles like the opportunity cost of parenthood. Indeed, one must be out of their mind to pursue parenthood just because tradition demands it. I am reminded of the title of a book on parenting: All Joy, No Fun. If you are not prepared for true joy, the lack of fun will bring great disappointment. Joy is reserved for those who are prepared to serve. Faithless countries with greater vote shares for conservative parties have certainly not experienced a baby boom as of late. As I see it, the association of faith and tradition has it all backwards. Deference to tradition is the exact opposite of faith in an active, living God. Rather: where the faithful do adhere to past wisdom, they do so out of discernment, not deference to past tradition.

Individuals stop worshipping with others before they stop praying. And loss of prayer precedes demographic decline.

The data supports this distinction. When I include church attendance in my regressions, it proves insignificant for fertility—whether or not prayer is also included. This could reflect data limitations, but it may indicate that interior transformation through active prayer, rather than social participation, drives the effect. My sense is that the insignificance is reflective of the dynamics of irreligiosity and demographic decline: Individuals stop worshipping with others before they stop praying. And loss of prayer precedes demographic decline. In today’s Europe, belief still exists outside of church pews. The body of the faithful, however, has disintegrated into many disjoint parts.

Why?

Many Europeans (perhaps unknowingly) have grown up to become existentialists: we create our identities on a blank sheet of paper. In ‘existentialism is a humanism’ Sartre writes: “man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world — and defines himself afterwards.” I sense that no generation that has felt this more strongly than mine, which came of age after the Cold War. When first conceived, such philosophy feels like freedom: It promises liberation from parental missteps, history’s errors and severs supposed obligations before citizenry and God. It is also redemptive: If we define ourselves, we need no longer call our selfishness as such. Our Augustinian brokenness is a construct, no longer caused by sin but imposed on us by an oppressive ideology. This is redemption without sacrifice. We are free.

Seen through the lens of existentialism, prayer is as effective as meditation or a self-help group. It becomes an act of self-expression, self-creation. Part of the personal project of curating among the pleasures in life. The greatest prize that this philosophy offers is the aesthetic: sublime music, the sensual as in romantic passionate love, grandiose architecture as in temples of art, enriching culinary experiences, and mere observation of nature. The aesthetic is not a small prize. God’s creation and the wealth of human experience that may live within it truly are wonderful.

The Power of Love

There existed a moment in my youth when the aesthetic experience—especially music—was all that I aspired to. I returned to faith, I believe, by discernment through the spirit. I perceived that the qualities of what is truly good and beautiful in life are not ordained or decided by human beings. Rather, what is truly good and beautiful reveals itself within reciprocal relationships whose essence is love. The one who serves brings goodness upon the one served: as in the performance of music, the sharing of food, the housing of others, in teaching where students offer their attention to receive their teacher’s intellect. No where has this become more apparent to me than in music: The secret of Bach’s music is not the rich harmonies but the dance. The secret of Mozart’s is expressing depth through the lightness of a child’s melody. Their music is a gift of love unto us—their listeners and performers—not an act of self-expression. Love makes us excellent without seeking appraisal. How is such love possible? In Genesis we learn: We are created in the image of God. We exist because of God’s abundant love. His love precedes Sartre’s blank paper conception of human existence. Later God affirms: ‘I have called you by name; you are Mine!’ Reading this, I am overcome by great relief and great clarity. If God created this world—you and me—because of love, then how can I not desire to serve that which He created in His image?

I cannot write well about these mysteries. It is only through music that I begin to fathom. This much I do know, however: liberty was given to all people because God loves. This does not mean that we must create our own identity. Where such confusion arises, it does not promote good. By usurping the role of Creator, we doubt that we need love. Faced by our own imperfections, we begin to doubt that pure love could exist. And when our project finally fails, we doubt that we deserve love. Only then, know that you are mistaken. We do not deserve. But we receive as a grace—through prayer. St. Paul writes: “Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances.” As a social scientist, I’m in no position to recommend prayer. But as a person of faith, I pray that you do.

Christopher Sandmann is Assistant Professor in Economics at the London School of Economics. You can follow his non-research writings at theholdupproblem.com.

1. Both Barro, McCleary (2003) and their critical appraisal in Durlauf, Kourtellos, Tan (2012) show that GDP growth negatively correlates with religious attendance.

2. For readers interested in the full econometric specification, detailed methodology, and robustness checks, see the complete analysis on my blog: https://theholdupproblem.substack.com/p/other-kingdoms